I am a Weyward, and wild inside.

2019: Under cover of darkness, Kate flees London for ramshackle Weyward Cottage, inherited from a great aunt she barely remembers. With its tumbling ivy and overgrown garden, the cottage is worlds away from the abusive partner who tormented Kate. But she begins to suspect that her great aunt had a secret. One that lurks in the bones of the cottage, hidden ever since the witch-hunts of the 17th century.

1619: Altha is awaiting trial for the murder of a local farmer who was stampeded to death by his herd. As a girl, Altha’s mother taught her their magic, a kind not rooted in spell casting but in a deep knowledge of the natural world. But unusual women have always been deemed dangerous, and as the evidence for witchcraft is set out against Altha, she knows it will take all of her powers to maintain her freedom.

1942: As World War II rages, Violet is trapped in her family’s grand, crumbling estate. Straitjacketed by societal convention, she longs for the robust education her brother receives––and for her mother, long deceased, who was rumored to have gone mad before her death. The only traces Violet has of her are a locket bearing the initial W and the word weyward scratched into the baseboard of her bedroom.

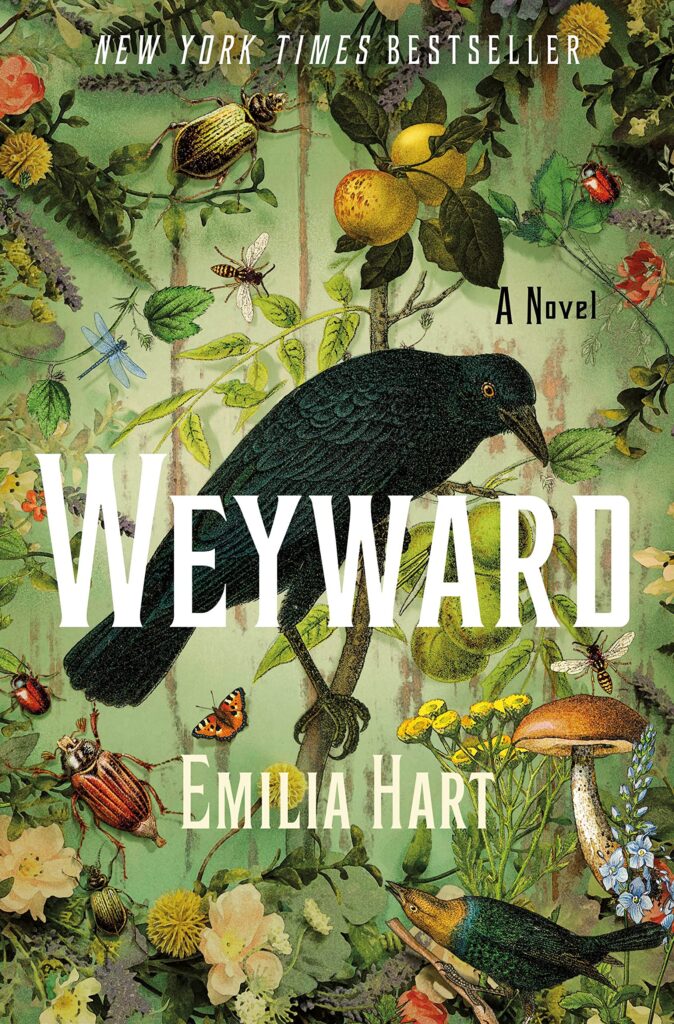

Weaving together the stories of three extraordinary women across five centuries, Emilia Hart’s Weyward is an enthralling novel of female resilience and the transformative power of the natural world.

Introduction

I must be honest here. What initially prompted me to pick up “Weyward” wasn’t the reviews or the synopsis; it was this stunning cover! This cover alone would entice me to return to this book repeatedly. Yet, when you delve into its pages, you stumble upon something I wasn’t entirely acquainted with but now cannot imagine my reading life without – “witcherature.”

“Perhaps one day (…) there will be a safer time, when women could walk the Earth, shining bright with power, and yet live.”

Overview

In Emilia Hart’s debut novel, we are introduced to Kate Ayres, a 29-year-old woman in 2019 who is meticulously planning her escape from both London and her abusive boyfriend. Her newfound refuge lies in the form of Weyward Cottage, a legacy left by her great-aunt Violet, a quirky entomologist who Kate scarcely remembers. This haven is nestled in the remote village of Crows Beck, Cumbria.

The narrative then transports us back to 1942, where we encounter 16-year-old Violet Ayres, trapped within the confines of her father’s Cumbrian estate, Orton Hall. She is under the watchful eyes of a governess and nanny, forbidden from venturing into the nearby village of Crows Beck or attending school. The reasons behind her father’s stringent rules remain shrouded in mystery. He disapproves of Violet’s affinity for the outdoors, her penchant for climbing trees, and her propensity to rescue animals. He fears she may be following in the footsteps of her late mother, who passed away when Violet was just a toddler.

Interwoven amidst Kate’s and Violet’s narratives is the first-person account of Altha, a young woman from Crows Beck facing a witchcraft trial in the year 1619.

These three timelines—2019, 1942, and 1619—intertwine, weaving together the journeys of Weyward’s women. This intricate tapestry keeps the tension high as each character grapples with danger and makes challenging decisions. As Kate and Violet gradually unveil their connections to other women of Weyward Cottage and the natural world, they both learn to lean on their inner reservoirs of strength.

“Witch. The word slithers from the mouth like a serpent, drips from the tongue as thick and black as tar. We never thought of ourselves as witches, my mother and I. For this was a word invented by men, a word that brings power to those that speak it, not those that it describes. A word that builds gallows and pyres, turns breathing women into corpses.”

Trigger Warnings

Content warnings in the realm of fantasy literature often tread a curious path, yet I find it necessary to illuminate aspects that could serve as potential triggers for fellow readers. Be advised that these warnings should be taken with care as I am not a licensed therapist and in no way could I identify everything. The following is what stuck out to me and other readers. The following might contain spoilers.

Domestic Abuse

There are intense scenes of physical and emotional abuse towards women.

Anxiety Disorder

One of our MCs struggles with this due to an abusive relationship.

Murder

This one is self-explanatory.

Parental Abuse

One of our MCs suffers from emotional parental abuse and neglect.

Abortion

There are multiple scenes of self-abortion throughout the novel.

Tropes in the Story:

- Emotional scars

- Forbidden Romance

- Magic

- Class Differences

- Tear Jerker

- Feminism

“The connections between and among women are the most feared, the most problematic, and the most potentially transforming force on the planet.”

Thoughts

So, what exactly is Witcherature? In essence, it’s the incorporation of witchy women in literature, typically involving female characters who draw upon a divine feminine strength to break free from patriarchal structures. While this book proved to be a challenging read for me, and some of the trigger warnings hit a few of my personal no-go areas, it stands out as one of my favorite reads of the year. Although it didn’t quite earn a 5-star rating like some of its contemporaries, the story itself was truly exceptional, profoundly inspiring, and wonderfully magical. With my inclination towards darker reads, this book’s contemporary setting thrusts realism right in your face, and for that reason alone, I’d strongly advise anyone considering this book to review the trigger warnings beforehand. The book can be startlingly realistic in its portrayals, and readers should be forewarned.

Now, you might assume that this is why the book fell short of a 5-star rating, but on the contrary, this is what made it even more commendable in my eyes. I could sense that the author genuinely cared about their subject matter and had a story they were passionate about sharing.

Dear reader, the reason this story lost a star, in my view, was the pacing. While it’s true that many historical fiction works tend to have a deliberate pace, this book left me somewhat disoriented. It features substantial time jumps from various directions, which can be quite the feat for any author. While I appreciate the concept and direction, I believe it fell short in execution.

Amidst the flurry of action across all three timelines, I found myself growing frustrated with the abrupt transitions. At some point, I even contemplated setting the book aside because I couldn’t establish a connection with any character; there simply wasn’t enough time spent with them to truly care about their fates. In a way, I couldn’t become emotionally invested, though I dearly wanted to.

Conclusion

While “Weyward” is undoubtedly a story that needs to be told and culminates as an absolute gem at the end, it takes quite a long time to reach that point. I understand that diamonds require time to form, but typically, we don’t have to witness the entire process of the earth crushing them.

“A great many things look different from a distance. Truth is like ugliness: you need to be close to see it.”

“I had nature in my heart, she said. Like she did, and her mother before her. There was something about us—the Weyward women—that bonded us more tightly with the natural world. We can feel it, she said, the same way we feel rage, sorrow, or joy. The animals, the birds, the plants—they let us in, recognizing us as one of their own. That is why roots and leaves yield so easily under our fingers, to form tonics that bring comfort and healing. That is why animals welcome our embrace. Why the crows—the ones who carry the sign—watch over us and do our bidding, why their touch brings our abilities into sharpest relief. Our ancestors—the women who walked these paths before us, before there were words for who they were—did not lie in the barren soil of the churchyard, encased in rotting wood. Instead, the Weyward bones rested in the woods, in the fells, where our flesh fed plants and flowers, where trees wrapped their roots around our skeletons. We did not need stonemasons to carve our names into rock as proof we had existed.

All we needed was to be returned to the wild.

This wildness inside gives us our name. It was men who marked us so, in the time when language was but a shoot curling from the earth. Weyward, they called us, when we would not submit, would not bend to their will. But we learned to wear the name with pride.”